Complex Dependencies in Infrastructure as Code

Investigating edge cases with Terraform, Pulumi, CloudFormation, and Statey

Infrastructure as code tools allow developers to automate their infrastructure in some incredible ways, but they also have their limitations. It may be surprising, but even some changes that may seem routine can actually cause these tools to attempt impossible operations. For instance, imagine you’re trying to create the resources defined by the following Terraform configuration:

resource "aws_security_group" "test" {

name = "test_group"

ingress {

from_port = 22

to_port = 22

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

egress {

from_port = 0

to_port = 0

protocol = "-1"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

}

resource "aws_instance" "test" {

ami = "ami-07d02ee1eeb0c996c"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

key_name = aws_key_pair.test.key_name

vpc_security_group_ids = [aws_security_group.test.id]

}This configuration simply creates a security group allowing SSH access from any IP address and all outbound access, then attaches it to a new AWS EC2 instance. You run terraform apply and everything gets created without an issue. You think back to all the time you’ve spent creating resources in the AWS dashboard and feel a rush of excitement for the future. Next you decide you want to add a description to the security group; how great it is that it’s just changing a line of code! You end up with this configuration for the security group:

resource "aws_security_group" "test" {

name = "test_group"

description = "This is used to restrict access to my instance. Managed by Terraform."

ingress {

from_port = 22

to_port = 22

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

egress {

from_port = 0

to_port = 0

protocol = "-1"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

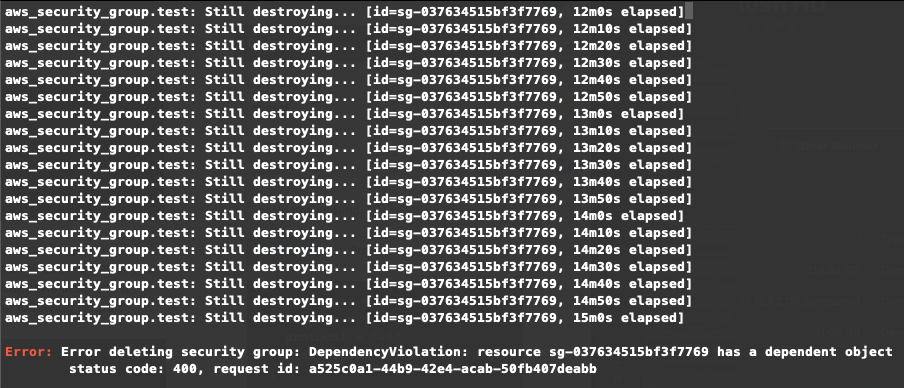

}You run terraform apply again and check the plan. The plan indicates that the security group will be deleted and recreated, and the instance’s security groups will be updated. All seems good; you approve the plan. Something is off, though—the security group deletion happens first, and it seems to be hanging for a long time. After about 15 minutes, you see the following output:

The message indicates that the security can’t be destroyed because the instance still depends on it. If you aren’t familiar with how infrastructure as code tools work this may seem pretty confusing—why are you having to worry about dependencies? Shouldn’t Terraform already be taking care of that?

All fair questions—and for the record, there’s more than one way to get around this sort of situation with every infrastructure as code tool on the market. The discussion of why Terraform isn’t respecting dependencies correctly in this case reveals some interesting things about how these tools work.

Why does this fail?

In a previous blog post I described at a very high level some of the fundamentals of how infrastructure as code tools build task graphs from two different states and sets of dependencies. While I encourage you to read the post as a primer, I’ll describe a few aspects that are relevant to the mystery of why Terraform doesn’t know how to handle our simple configuration change. All infrastructure-as-code tools are stateful—they use both the existing set of resources and your desired configuration to render some sort of “plan” of how they’re going to migrate from one to the other. This plan can be thought of as a graph of transitions for each of the resources defined in the configuration or state. When creating new resources, those that depend on other resources must be created after them. When deleting resources, those that depend on other resources must be deleted before them. When infrastructure as code tools execute these plans, it should leave all defined resources in the states defined by their configuration.

That may all sound fairly abstract, but a picture is worth a thousand words; I wrote an infrastructure as code tool called statey that largely replicates the core logic of Terraform, so I used it to generate some visualizations that help tell the story of what’s happening. This is what the task graph looks like when applying the original configuration above:

This makes a good amount of sense: our instance depends on both a key pair (not included in the configuration for brevity, check the repo to see the definition) and a security group. We can see that it gets created after those resources. If we want to destroy the infrastructure, the plan looks like this:

The dependencies are reversed, which should also make some sense. As we can infer from the original issue we encountered with Terraform: a security group cannot be deleted when it has other objects depending on it. The instance is actively depending on it, so if we always tried to delete the security group first the operation would never succeed. This logic is applied in general to any dependency when deleting resources in infrastructure as code tools.

In considering why our terraform operation failed above, it is informative to take a look at the task graph for that plan:

The red arrow indicates an ignored dependency. There are two places where dependencies come from when building a task graph: the dependencies implied by the configuration, and the reverse of the dependencies implied by the previous configuration. However, it’s not uncommon for the reversed dependencies of the previous configuration to create a dependency loop among the tasks. For this reason, those dependencies are ignored if they cause loops during planning. Another important note here that is common to both statey and Terraform is that the security group must be deleted before it is recreated. If this wasn’t the case, the ignored dependency could be respected without creating any loops. There’s another domain-specific fact that is relevant as well: we originally defined our security group with an explicit name. AWS won’t allow us to create two security groups with the same name in the same region and account, so even if we weren’t limited on the tool level we couldn’t recreate the security group before deleting it. Most or all AWS resources should have some option to randomize names that must be unique; in this case we can use name_prefix instead.

This is basically the root of the problem—when infrastructure as code tools encounter a loop in the task graph, they ignore certain dependencies rather than present the user with an error—in general this approach works in many different cases. If the security group was just being updated rather than recreated, for example, everything would go through just fine. When they’re forced to ignore dependencies, the behavior of infra-as-code tools is not always defined. In this case, Terraform attempts to delete a security group that will never be able to be deleted until the instance is detached. Of course, the instance will never be detached until the security group is deleted so manual intervention will be required.

Resolving the Issue with Terraform (or Statey)

Knowing the issue, there’s a couple different approaches we can take to resolve this in our terraform configuration. One of the issues mentioned was that the security group had to be deleted before it could be recreated—this is because in Terraform, only one resource can live under a given identifier at any given time. By identifier, I mean the name we gave to the resource—in this case test. If we change this, Terraform won’t require that we delete the existing security group before creating a new one. The new security group gets created under a new name, associated with the instance, and the old one gets destroyed. The task graph looks like this:

The yellow arrow indicates an optional dependency that is being respected. If we apply this configuration, all operations will complete successfully. The new terraform configuration making this change would look like this:

resource "aws_security_group" "test_2" {

name_prefix = "test_group"

description = "This is used to restrict access to my instance. Managed by Terraform."

ingress {

from_port = 22

to_port = 22

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

egress {

from_port = 0

to_port = 0

protocol = "-1"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

}

resource "aws_instance" "test" {

ami = "ami-07d02ee1eeb0c996c"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

key_name = aws_key_pair.test.key_name

vpc_security_group_ids = [aws_security_group.test_2.id]

}This approach works, but it’s a little inconvenient. Since resources are referenced in Terraform by their identifiers, changing the identifier requires changing all references to the resource as well (not to mention adding some unsightly suffix).

There is also another approach that, while not suitable for most situations, can also get around the issue without having to change a bunch of identifiers in dependent code. Destroying and creating resources does always happen in the correct order, so if we are ok with also recreating the instance, that will also get around the issue. For example, if we use the terraform taint command or anything else to force recreation of the instance, the plan will look like this:

This one is interesting to inspect: we can see that the current instance gets deleted first, then the security group deletion and creation happen in succession after that. At that point, the new instance gets created. One of many examples of configuration changes that could force this:

resource "aws_instance" "test" {

ami = "ami-07d02ee1eeb0c996c"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

key_name = aws_key_pair.test.key_name

vpc_security_group_ids = [aws_security_group.test.id]

user_data = "#"

}Now, this would probably be difficult to figure out unless you really had a good understanding of how infrastructure as code tools operate before coming across this blog post. It does emphasize, however, that the problem we’re running into is not always visible. This approach probably does not make sense for most real use-cases, though. It’s fine to recreate our instance if we just created it as a test, but probably not if it’s serving something in production.

Though it’s good that there are approaches available to work around this limitation with some infrastructure as code tools, there are also some that are able to avoid the issue altogether (given some constraints).

How Pulumi and Cloudformation Handle the Issue

Though this is a problem with Terraform, it’s not necessarily inherent to infrastructure as code as other tools have shown. I am a big fan of Pulumi, so I was really curious to see how it handles this issue. I had read in the Pulumi Resources Documentation that there was a concept of recreating resources before deleting them, so I was curious about that. If we use the exact same configuration we started with, we will run into the same issue:

security_group = aws.ec2.SecurityGroup(

"test_sg",

name="test_sg",

description="This is my security group.",

ingress=[

{

"protocol": "tcp",

"from_port": 22,

"to_port": 22,

"cidr_blocks": ["0.0.0.0/0"],

}

],

egress=[

{"protocol": "-1", "from_port": 0, "to_port": 0, "cidr_blocks": ["0.0.0.0/0"]}

],

)

instance = aws.ec2.Instance(

"test_instance",

ami="ami-07d02ee1eeb0c996c",

instance_type="t2.micro",

key_name=key.key_name,

vpc_security_group_ids=[security_group.id],

)The deleting operation will run for about 15 minutes, and then it will fail with a dependency violation. The difference, however, is that if we do not specify a name and let pulumi pick one for us:

security_group = aws.ec2.SecurityGroup(

"test_sg",

description="This is my security group.",

ingress=[

{

"protocol": "tcp",

"from_port": 22,

"to_port": 22,

"cidr_blocks": ["0.0.0.0/0"],

}

],

egress=[

{"protocol": "-1", "from_port": 0, "to_port": 0, "cidr_blocks": ["0.0.0.0/0"]}

],

)In this case, when creating our infrastructure we’ll find that everything goes through properly. If you watch the execution as it happens, you’ll be able to see that the new security group creation happens first, then the update to the instance, then finally the deletion of the old security group.

I was also curious about how AWS CloudFormation, their native infrastructure as code solution, handles these types of cases. It was a good excuse for me to try out the new AWS CDK (Cloud Development Kit) a bit; I discovered it very recently for the first time. The code there looks pretty similar to Pulumi:

security_group = ec2.SecurityGroup(

self,

"test_sg",

vpc=vpc,

allow_all_outbound=True,

)

security_group.add_ingress_rule(ec2.Peer.any_ipv4(), ec2.Port.tcp(22))

image = ec2.AmazonLinuxImage()

instance = ec2.Instance(

self,

"test_instance",

machine_image=image,

instance_type=ec2.InstanceType("t2.micro"),

key_name="app_key-d2f12cf",

vpc=vpc,

security_group=security_group,

)It appears that CloudFormation (via a template compiled from this CDK code) has the same behavior as Pulumi—it creates a new resource first, then deletes the old one. The CDK doesn’t even provide an option to set an explicit name; it will always add a suffix.

The reasons why these tools behave differently have to do with technical differences in how the state of resources are stored internally. Essentially, these differences result in the plan looking like it did when we changed the ID of the security group to resolve the original issue with Terraform:

Recreating infrastructure before deleting old versions is generally presented by Pulumi as a way to avoid downtime when deploying infrastructure, and it works well for that too. In addition, however, the ability to resolve this sort of dependency issue without user intervention is a great feature in these two tools, and makes them more robust to a whole range of non-obvious issues. That said, properly making use of this sort of behavior requires: first, that whatever provides the resource actually implements the ability for resources to have non-deterministic identifiers. Also, it requires being aware of and making use of that functionality in all resources. AWS resources all provide this, but one of the great things about Pulumi and Terraform is they can also be used to put together systems that span across many types of resource providers. When working with other resource providers, this sort of behavior is not guaranteed. There also does not appear to be very good tooling or communication around this issue at the moment—a user not familiar with best-practices might unintentionally void this behavior by setting an explicit identifier for their resource. The Pulumi documentation mostly does a good job of noting these distinctions though.

What The Future Might Look Like

Going back to the original Terraform example—if we didn’t want to mess with identifiers or any tricks to correct the plan, there’s another approach we could take that doesn’t even require having to randomize resource names: we could do the migration in two steps. In our configuration, we’d first simply remove the security group association from the instance, like so:

resource "aws_instance" "test" {

ami = "ami-07d02ee1eeb0c996c"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

key_name = aws_key_pair.test.key_name

vpc_security_group_ids = []

}This will allow the plan to go through correctly like this:

We can then change the configuration to reassociate the security group with the instance (as it no longer needs to be modified), and that change will occur without an issue as well. This touches on an interesting limitation that all infrastructure codes on the market currently have: they are all entirely declarative, meaning they don’t give us as users the opportunity to encode all of our domain knowledge into the program. Even if I know in advance the best way to do this is in two steps (and in some cases, that may be the only way), the program doesn’t provide any way for me to tell it that or handle that sort of multi-step transition.

In my opinion the really cool possibilities of what infrastructure as code can do start to open up when code written on top of them can be truly reusable. One aspect of that reusability, however, is that is has to operate on some level like a black box—the less the user is expected to understand about the tool or other domain in order to use it, the more accessible it will be for developers of all experience levels to deploy and maintain scalable and secure applications in the cloud. If it were possible for us as developers to encode some of our domain knowledge into the planning logic to handle some of these tricky cases, the sky’s the limit to what could be implemented on top of infrastructure as code tools. Pulumi recently released their Automation API. I haven’t gotten much of a chance to play with it yet, but it opens up the awesome possibility to write infrastructure management services and tools from scratch. This works really well for creating and destroying stacks from scratch, but I am curious about how well it handles updates. As a developer, we can interactively look at a plan and determine whether anything looks out of place. If we’re applying plans through automation, this human-in-the-loop no longer exists. Probably there is an API or will be to do validation of plans with business rules already, but allowing developers to customize the planning process so that issues can be avoided altogether would be an amazing next step in the evolution of infrastructure as code.

Conclusion

Infrastructure as code tools are incredibly powerful, and they will only get better as time goes on. I thought it was interesting to dive into this issue because it reveals some interesting distinctions between different tools, but ultimately users should not have to be aware of these sorts of nuances. It’s excellent that some of the modern tools have already developed approaches that eliminate the issue I presented here in some cases, but we certainly haven’t yet seen everything that these tools will be able to do.

If you want to see all of the code I used to research this blog post & generate the plan visualizations, check it out on Github!